Indonesia’s wildly diverse eco-systems harbour an incredible variety of animals. Orangutans are the stars of the show at Camp Leakey.

A long hairy arm extends over my shoulder, fingers tickle my torso. I reach around to hold her hand behind my back, like we’re canoodling at the cinema hoping no one will notice. She turns to me and smiles. Her mouth is full of stinky sweet durian and her lower lip protrudes comically.

It’s an intimate moment and I return the smile, completely smitten. Siswe and I are sharing a simple wooden bench on the veranda of Dr. Birute Galdikas’ home at Camp Leakey in Borneo’s Tanjung Puting National Park. Siswe is approximately 35 years old, the local troupe’s alpha orangutan female and as strong as ten men. ‘She could dislocate your arm as easily as you would snap a twig you know,’ says Galdikas, ‘but she likes men, particularly older men.’ I don’t know if I’ve just been insulted or complimented. I’m seated between two alpha females and feel that if I don’t show proper respect, I could be in big trouble. It’s not as if I haven’t been exposed to enough already.

Borneo’s rainforests aren’t for the faint-hearted. I’ve travelled two hours on a small boat up a river full of crocodiles to get here. Venomous snakes are everywhere, leeches too. Borneo is alive with things that bite, sting or suck. If I trip on a boardwalk and fall into the surrounding swamp that encompasses Camp Leakey, I may not live to tell the tale. But I’ve come to meet one of my human heroes, Dr. Birute Galdikas and to get up close and personal with a few other animal heroes, the critically endangered orangutans of Indonesia. The risks involved are minimal compared to the rewards gained.

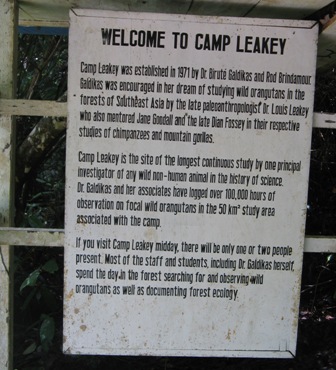

Once there were three. Now there is one remaining Leakey angel still working in the field. Jane Goodall retired from studying chimpanzees in Tanzania over twenty years ago to launch her own wildlife preservation foundation. Dian Fossey was murdered in 1985 while studying mountain gorillas in Rwanda. Birute Galdikas continues her field research where it all started in 1971, in Indonesia’s Kalimantan Province on the island of Borneo. Her research station in Tanjung Puting National Park is called Camp Leakey in honour of her mentor, the great anthropologist Louis Leakey.

Before meeting Galdikas I wander around Camp Leakey with a few fellow travellers. The orangutans are supplied with fruits twice a day at various feeding stations arrayed in the surrounding forest, enough to supplement their diet but not enough to encourage dependency in place of natural foraging. The hours between feeding times allow visitors to explore the camp unsupervised. I find a black-handed gibbon positioned in a small tree outside the cook’s cabin. Normally gibbons are high up in a tree as possible, invisible in the upper canopy. Without excellent vision, binoculars and luck, they’re difficult to spot. This gibbon posed for me from a few metres away, looking for companionship or a handout or both.

Not so the proboscis monkeys. They sit in the trees along the river in full view, catching the morning sun’s rays. The males sport continually erect penises, ever ready to service the females in their troupe. The local Dayaks call them the Dutch monkeys, drawing attention to the resemblance of the monkey’s protuberant noses to those of the country’s former colonial masters.

A family of wild pigs scampered about. Piglets squeal with delight in an open area near the dining room. One of the adult female pigs is blind; she has no trouble avoiding tree stumps, unlike me while I continually trip over tree roots in the dimly lit forest.

Siswe is one of Galdikas’ favourites and a regular at Camp Leakey. Though essentially a wild animal, she has adapted to occasional human company. ‘Sometimes I hear her banging around on my roof while I’m trying to sleep,’ adds Galdikas, ‘but usually she’s off somewhere in the forest reminding other orangutans who’s boss.’ It’s difficult to imagine Siswe as a tyrant. Instead her gentle caresses lead me to believe otherwise. Her giant hand rests easily on my shoulder, her fingers are a bit grotty and sticky from the sugary durian, like a child’s hand that has spent too much time in the lolly jar. Her intelligence is comparable to that of a three year old human child’s too. Like most kids, Siswe charms, cajoles, manipulates emotions and throws temper tantrums, yet I detect wisdom in her eyes that comes from learned experience. She is a picture of calm sitting next to me yet still unpredictable, hence Galdikas’ warning.

The light grows crepuscular; night descends quickly at this latitude. Heavy rain resumes. Siswe sighs melodramatically, scratches her head with her left hand, leaving her right around my waist giving me a slight squeeze. ‘She gets depressed when it rains,’ says Galdikas, her shoulders slump in sympathy with Siswe’s glum attitude. I find this ironic, they both live in a rainforest. ‘Maybe you two need to move to a drier climate,’ I suggest. Galdikas has a hearty frequent laugh. Though her reputation for not suffering fools gladly puts her in strife with logging and mining companies, I find her an amiable companion. I’m on her side of the ecological argument after all. When Soeharto was president of Indonesia, Galdikas was kidnapped and beaten. Her position in Indonesia was a frequent topic during government cabinet meetings, deportation being a regular discussion point. Threats continue to thwart her work to save both the rainforest environment and all the creatures that live in it but now her work is supported by both the police and forestry authorities. She was given Indonesia’s Hero of the Earth award as national recognition for her work to save not only orangutans but all remaining wild habitats left in Indonesia.

Illegal logging and mining jeopardise the park’s boundaries though lately the damage in the park itself has been minimal. Not so outside the park. ‘Not far from where you’re staying is a huge palm oil plantation. The young male orangutan you saw outside your cabin yesterday has nowhere else to go so he’s travelling along the river looking for somewhere to cross into the park. There’s no food or shelter for him or other orangutans on the opposite side of the river,’ she tells me. ‘Gold mining upriver is polluting the eco-system too.’ I worry for the local Dayak people who live on, wash in, drink from and fish out of the river. Mercury poisoning is a real long-term threat. Galdikas’ mood shifts, not just from the rain, ‘The whole system here is so caught up in corruption and greed. I’ve been fighting against it for almost forty years, saving 95,000 hectares of land as a buffer for the park but the destruction continues. We have perhaps 4,000 or 5,000 orangutans left in Borneo, fewer than a 1,000 in Sumatra. Unless the world does something quickly, they may not survive. I do what I can but it’s not enough.’ Galdikas cares for approximately 300 orangutans in her sanctuary. They are protected by 200 local employees. Her foundation runs by the sniff of an oily rag, margins are tight, costs increase and her income is derived solely through donations.

I look at Siswe chewing her durian while we sit out the storm. She leans against me as if I can keep the raindrops away. Galdikas sips her coffee while pausing to collect her thoughts. Reality has intruded into the magic and the rain has dampened my mood too.

I am sitting on a rustic wooden bench with one of the world’s leading anthropologists and one of its rarest apes. The combination this represents could not for me be more pertinent. Here in one of the planet’s few remaining wildernesses, my thoughts focus on its future. Galdikas knows what she’s talking about. Her project has recorded more than 100,000 hours of observation of a single mammalian species, the longest ever in the history of scientific field research. In addition to direct study of orangutans and other primates and monkeys, Galdikas and her team have studied regional ecology since 1971. If someone more qualified to speak the truth about the decimation of rainforest habitats throughout the world exists, Galdikas would trump him. Her expertise is unparalleled. ‘The main problem in Kalimantan is the palm oil plantations. Poaching is more of a problem in Sarawak and Sabah. While the logging clears the land, the logging roads allow access to the hunters hired by the logging companies.’ Her conclusions are based on years of experience. Again I am humbled by her stoicism. Lesser minds would have given up long ago. Galdikas’ intellect, compassion and energy are remarkably constant. She breaks into my thoughts. ‘And now it’s time we headed to the dining room, the third bell just sounded and we’re making the staff late for their dinner. They don’t like it when I’m late and they won’t start eating without me.’ Her employees will wait for Galdikas to eat, knowing how hard she works they look after her and show their respect waiting for the boss.

Sharing dinner in the communal dining room, she insists that visitors stand and recount a brief history of how they came to be there, their work and family backgrounds. It’s an important custom for the Dayak people. Galdikas translates my words into Bahasa Indonesian. I explain that I am a writer interested in Indonesia’s wonderful flora and fauna and that I have come a long way to meet Dr. Galdikas and hopefully observe the work being done at Camp Leakey to preserve Indonesia’s remaining wild forests. I have come to thank them all for their hard work and promise to help spread the word about what they do. They in turn thank me and welcome me to their land. Galdikas says, ‘You must be hungry, so let’s eat. I’m starving.’

After midnight I reboard my rickety boat, and head downstream to Rimba Orangutan Lodge. I sit on the top deck under a canvas shelter, peering into a small circle of brightness illuminated by the boat’s single light globe. Crocodile eyes cast reddish-orange reflections. Fireflies flutter around me. A water monitor lizard swims quickly into tall reeds. I write more notes. Before I was first introduced to Siswe on a path outside Galdikas’ house, I met a younger female, Princess. Of all the orangutans I encountered at Camp Leakey, Princess is the most famous. Sir David Attenborough filmed her while she paddled a boat across a small river. No one taught her to do it. Orangutans don’t swim. They hitch rides on floating logs… or they learn to paddle a boat. Princess copied one of the workers at Camp Leakey while he rowed a small boat from one side of a stream to another. Princess’ feat of ingenuity was the first recorded instance of an ape using a boat in the same manner as a human. I also met Princess’ infants, Percy and Putri. No doubt Percy and Putri will begin operating a ferry service in the near future given their mother’s natural boating skills.

Finally I return to my cabin once the boat is safely moored back at Rimba Orangutan Lodge. I’ve been allocated Julia Roberts’ cabin. My guide, a long time employee, announced enthusiastically upon my arrival at the airport a few days prior that, ‘You are sleeping in Julia Roberts’ bed!’ I was surprised and commented, ‘But she stayed here ten years ago when that documentary was made,’ referring to the documentary film Roberts starred in while she drew attention to the orangutan’s plight. ‘Yes, but it is a new mattress,’ he confirmed. I sleep very well in Julia Roberts’ bed.

Tom Neal Tacker travelled courtesy of Garuda Indonesia Airways and Eco Lodges Indonesia.

Naked Facts:

Garuda Indonesia flies from Amsterdam, most Asian capital cities, Melbourne and Sydney to Jakarta for easy connections to most Indonesian centres. Express Air flies daily from Jakarta to Pangkalan Bun in southern Kalimantan. Eco-Lodges Indonesia arranges land transport to Kumai (45 minutes drive) and river transport (2.5 hours) from Kumai to Rimba Orangutan Lodge at the edge of Tanjung Puting National Park. All national park entry fees are included in Eco-Lodges Indonesia package rates. Costs per day inclusive of park fees, transport by river boat to and from Camp Leakey (2 hours), a superior room with ensuite bathroom and most meals is approximately USD$250 per day. Transport from Kumai to Rimba Lodge is USD$110 for 1 to 4 passengers.

Non-profit Eco-Lodges Indonesia, the only Green Globe accredited accommodation group in Indonesia is based at Udayana Lodge, Jimbaran Bay, Bali. Eco-Lodges Indonesia operates according to Australian management practice with locally employed supervisory staff. Profits are spent preserving local habitats and endangered species rescue operations.