There’s so much more to Cambodia than day-tripping to Angkor Wat.

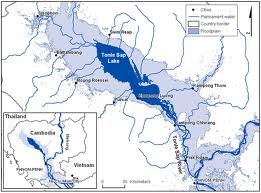

When the rainy season reaches full stride during the torrid Cambodian summer, life here changes rapidly. Fickle climate change has increased unpredictability. Now, heavy rain may fall at any time, though January through May is normally dry. By August however the dust has turned to mud, roads are almost impassable and a farmer’s wishful thoughts turn to the Mekong River and its tributary lake, the great Tonle Sap. The flood down the Mekong can be intense so that water begins to back up the Tonle Sap channel, annually refilling this amorphously shallow lake.

Fish fatten, rice paddies flourish and the people eat well. Sadly, new dams upstream in southern China where the Mekong begins its journey through Southeast Asia present potentially damaging environmental problems in a country that has already experienced more than most. Despite the flooding, the lake level is at a historic low and fish harvests are down.

To recount a Cambodian chronology is to reflect on years of hardship. In the late 1960s, great swathes of countryside were fire-bombed, whole towns were reduced to rubble. During the 1970s, Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge murdered some three million people. The Vietnamese killed most of the wildlife and bombed temples in the 1980s. Then the Thais, the Chinese and the Vietnamese purloined many of the country’s artworks in the 1990s. Add rampant local corruption to the tale and sadness becomes the overarching narrative.

Most travellers in Siem Reap spend a few days at the great temples, undoubtedly among Asia’s magnificent sights. Given the scores of camera-toting tourists lined up at the artificial lake in front of Angkor Wat waiting for the requisite dawn or dusk money shot, it continues to be a global tourism drawcard.

Other temples such as Angkor Thom and Bayon attract similar sized crowds. Angelina Jolie fans at Ta Prohm temple duly recreate scenes from the Lara Croft Tomb Raider film shot here in 2001.

Gigantic fig vines twist around ancient stones recreating an alluring film set atmosphere.

Relatively few visitors are aware that the Siem Reap region contains over 200 temples, most of them infrequently seen. To gain an appreciation of what lies waiting to be explored, head to Phnom Bakheng atop Temple Mountain and be amazed at the sweeping vista, a sure invitation to venture further a field.

I spend a hot humid afternoon at Beng Mealea and Koh Ker temples. My guide, a survivor from Pol Pot’s decimation of the educated elite, mentions that a dark corridor I am tempted to explore at Beng Mealea is rife with ‘scorpions and cobras’ and that it is unwise to proceed.

Landmines scattered around this area have only recently been removed with the help of a German aid organisation.

Carried away again by the tomb raiding atmosphere, I completely forget that it’s a jungle out here. There is no one else about.

At Bantey Srey, a lovely pink-hued sandstone temple, known also as the ‘Citadel of the Women’ for its delicately carved inlays of village women, we are also alone. These sites are only 90 minute’s bone-rattling drive from Angkor Wat, but off the beaten track. There are numerous nearly forgotten places, just as hauntingly beautiful as Angkor Wat but minus thousands of tourists.

While the less popular temples are undeniably stunning, eerily quiet and peaceful, after a few days I’ve reached temple overload. A sort of ‘not another bloody temple’ experience akin to too many European cathedrals in a week or too many masterpieces in the Louvre museum in a day. In short, I’m not appreciating what I should be appreciating and need a break. I consult with my hosts and ask their advice.

Prepared for a week’s touring around Siem Reap to focus on Angkor Wat and to sample some of Cambodia’s intriguing cuisine, I am fortunate instead to be allowed a glimpse into present day realities, a privilege granted by the Hotel de la Paix. I could have stayed at any one of numerous hotels in Siem Reap, the pickings are ripe. Admittedly, the de la Paix is a 5-star hotel, slick and cool with efficient plumbing and an in-house generator that kicks in when the town’s power supply shuts down, which occurred daily while I was there. A reliable internet connection, sensational food and a bar that wouldn’t look out of place in Miami’s South Beach complete the picture. It’s also run by people with big hearts and keen social awareness. While many hotel managers in Siem Reap have retrenched staff during the global financial downturn, the de la Paix management team took a collective pay cut in order to retain all part time and casual workers. One income supports a dozen people around Siem Reap, a fact other hoteliers have callously ignored.

Among many experiences available to travellers: cultural wonders, food tourism, river boating, beach havens, wildlife and eco-tourism spring immediately to mind, Cambodians themselves inspire hope. I believe two choices await visitors to Cambodia. Wear blinders or go with eyes open to daily reality. For me, a visit to Cambodia is emotionally charged. Each day I laugh hysterically or sob uncontrollably, usually both.

My itinerary is altered and my impressions instantly change. First up is the Hotel de la Paix Sewing Training Centre, founded by volunteers to keep women employed as full-time seamstresses or designers rather than as construction site labourers earning less than USD $1 per day making bricks. The following day, I visit the Green Geckos Project, also supported by the hotel. It’s an orphanage for abandoned children, keeping them off the streets from a life of begging or worse. At a special English school, again partially funded by the hotel with over 400 students, helping to expand employment potential in a very tight labour market, I give impromptu lessons in English much to the amusement of the students. Evidently they aren’t given many opportunities to hear a foreigner make a fool of himself in public while he tries to explain the subjunctive text. I’ve gone from temples to tears to laughter in two days.

None of these efforts is mentioned in the hotel’s publicity material, though guests are encouraged to get involved if they wish, discreet inquiries lead to open doors. The Hotel de la Paix commits to charity because it’s the right thing to do. Profits flow on from good works, hopefully. In this hotel’s case, they do. Operating at over 80% capacity, both the restaurant and bar are full every night. Other 5-star hotels I visit are nearly empty, an example of good karma in action. I suspect that a lot of hard work behind the scenes helps.

At Green Geckos, I meet with founders Tania Palmer, an Australian from Sydney and her Cambodian husband Rem Poum. Unlike other orphanages, Green Geckos operates as a sanctuary and school for kids whose parents are alive but have abandoned them to the streets. They are the forgotten offspring of living parents trapped by drug addiction or the sex trade, incapable of supporting their children. Until Green Geckos rescued them from the streets most had never been to school. Palmer tells me that, ‘We’ve had three independent assessments done by volunteer child psychologists. I was told that each of our kids has been physically abused, some of them sexually.’

Green Geckos send their kids to the local school where they follow the national curriculum. At 3pm they return home to two more hours of school to learn English and other skills. They share the duties of preparing the evening meal, the older children helping to supervise the younger ones. One hundred and three kids live here, all rescued from a miserable life on the streets of Siem Reap. Some parents try to stay involved in their children’s lives but most don’t. They voluntarily place their kids at Green Geckos though Palmer assures me that it’s a difficult process. ‘We try to help the parents escape from horrible circumstances but some are so addicted to alcohol, drugs or worse that it’s an almost impossible task. Some of our kids sleep here because it’s not safe at home but spend some of the weekends with their parents to maintain some family connection. A few parents struggle to change their lives and we’re able to help them as best we can, my husband Prem is a social worker with a network of other local charities. A couple of them have been able to change their lives but still can’t look after their children. Some are handicapped due to war injuries. I’m sure that most of the parents have suffered abuse themselves and they can’t earn enough money to support themselves much less their children.’

She gestures at the kids as they return from school. I notice one boy sit at a nearby table and immediately open his notebook. ‘Watch him,’ Palmer instructs. ‘He lost his father last week to a drug overdose. He’s 13, a lovely boy. He didn’t attend his father’s funeral. We didn’t force him to go either. His father beat him every day of his life, he’s so insecure and unloved but he’s coming out of his shell now. His story is so much like all the others here.’ The look on the boy’s face tells me much, a hidden sadness, deep-rooted and permanent. Palmer continues, ‘We think that we’ve got all the kids off the streets of Siem Reap now though by no means do all the kids not in our care go to school. This global financial crisis is taking its toll on the countryside. More people are leaving their villages to find work in Siem Reap. The pity is that there is no work here either.’

The boy’s story parallels Cambodia’s. Pervasive sadness is readily evident. How can there not be? The genocide wiped out a third of the population. A whole generation bears the ultimate cost; many survivors have no living relatives. The emotional damage I observe in their faces overwhelms me. Strangers I meet tell me that they lost parents, siblings, grandparents and now they’re completely alone, disconnected from their family history but bound by the country’s past.

At Angkor Wat I talk to kids as young as five selling postcards and cheap jewellery to tourists. ‘Where do you go to school?’ I ask them via my guide acting as translator. ‘We have no school today,’ they reply. My guide tells me they always say that, reneging on school, working instead around the temples paying off the police to gain access and making less than USD $2 per day if they’re lucky. The money buys them a little food but most of it goes to their families. I invite two of them to join us for lunch, hoping that this one meal will be enough. I don’t want to give money as I’m not sure if it will go to their parents’ drug habits or worse. They smile while they devour noodles and vegetables with a fried egg on top. I buy them fresh coconuts to drink and watch them walk away in the extreme heat, skinny legs barely coping with the weight of trays laden with tourist tat. Back in my cocooned room at the de la Paix, I weep.

I spend a full day with Nick Butler, manager for the Angkor Center for Conservation of Biodiversity (ACCB) and the Sam Veasna Center. His role is to train and organise a team of local guides to run the Center’s eco-tours while spreading the message that Cambodia harbours a shrinking though incredibly diverse eco-system. When I ask him about the Vietnamese massacre of Cambodian wildlife, he concurs. ‘After the Pol Pot regime finally ended, the Vietnamese came in and nearly wiped out vast areas of pristine wilderness. There was an area in the northeast that was known as the ‘Serengeti of Asia’ because of its population of migratory herd animals and predators such as tigers. But most of it is gone now because of logging and deforestation due to bombing raids. The Vietnamese and Chinese trade in endangered species has certainly nailed down the coffin lids.’ We’re in his clapped out 4WD bouncing through enormous potholes on flooded roads on our way to Ang Tropaeng Thmor, a bird sanctuary two and a half hours drive from Siem Reap. Rare water birds flock here, a reservoir dating to Angkorian times with the largest concentration of Sarus Cranes and Lesser Adjutant Storks in Southeast Asia.

It’s also home for the endangered Eld’s deer. But water levels are high and the birds are widely dispersed, the deer are invisible in dense undergrowth. Perched on a muddy embankment peering in vain for Sarus Cranes through humidity clouded binoculars, I watch instead a motley crew of fishermen fling nets into the lake. They wade chest deep pulling in a meagre catch.

A few rare Milky Storks, white like ghosts, shadow the fishermen patiently pursuing escaped fish. For a minute I forget about the misery that preys on my mind. The bucolic scenery is like a heart tonic.

I joke with Butler that, ‘It’s hard work on the posterior this twitching for Sore-ass Cranes business.’ We laugh, give up bird watching for the day and share a small bunch of bananas while squatting on our heels in the sticky ooze. Butler tells me that he’ll never look at this endangered crane the same way again. Late afternoon thunderclouds roll in, rain pelts down and we run for the truck.

Out of the rain again, driving through flooded fields, Butler tells me how Ang Tropaeng Thmor has been saved. ‘Some of it’s due to luck. The local people need this water to help feed their families but corrupt property developers with offshore funds have their eyes on it for possible resort potential. It’s not as bad as what’s happening in the south though.’ Returning to Siem Reap we attempt an alternate route to avoid the worst of the deepening potholes. Passing through a colourful though clearly impoverished village, rickety wooden shacks surround a modest Buddhist temple, the town’s focal point. I prod Butler for more of his insider knowledge about corruption and its effect on wildlife. ’Government ministers who should know better have attained land in national parks for upmarket resorts,’ he affirms, shifting into 4 wheel drive as we navigate another flooded road, detouring into a paddy field. On the same theme he adds, ‘Illegal logging continues in the Cardamom Mountains, the proceeds go right out of the country. If there are many Indochinese tigers left in Cambodia, they live there. No one knows how many but there’s little chance of survival if their habitat is continually under threat.’

Back in Siem Reap, my mood has also shifted to low gear. Cambodia contains amazing beauty amid the widespread misery, a juxtaposition that is frustratingly enervating. I decide to stop for a pick-me-up drink at Miss Wong bar, owned by a New Zealander I met on my first night in Siem Reap. He worked as an agriculture and media advisor before deciding to open this funky little gem in The Lane not far from the Old Market. Advertised as ‘A Sip of Old Shanghai’, it’s a fun place popular with Siem Reap’s small ex-pat community. Coincidentally, one of the de la Paix’s senior managers joins me and I’m happy to catch up with him again. When I recount my day of alternating highs and lows of bird-watching in the mud, he tells me a story about falling into a canal on his way home the night before. Siem Reap’s streets are poorly lit. Incessant rain has turned roadside canals into small rivers and nocturnal journeys have become perilous as a consequence. His tuk-tuk driver misjudged a turning and drove into a canal. ‘No one was hurt but we made a lot of noise. Neighbours came out of their homes to investigate the commotion.’ He sips from his beer. ‘They all stood there and pissed themselves laughing. No help whatsoever! I was soaked to the skin and ruined a nice pair of shoes.’ I imagine the scene. He’s a very dapper fellow, and laugh into my rum sour. The incident takes on hilarious aspects. ‘I’m tired, long day at work. You’re fixed for tomorrow’s flight back to Bangkok right?’ he asks. I remember that I’m leaving Cambodia the following day. The time here has passed quickly.

After midnight I wander home to the de la Paix refuge, reflecting again on all I have seen in one roller-coaster of an emotional week. Near the old market a teenaged girl offers a massage. ‘Hello mister. You want massage? Hah? Cheap, very nice.’ She tries to smile alluringly but looks merely desperate. Then a pock-marked young man offers drugs and a massage, ‘Hey mister. You like smoke hash? Massage? You want?’ I spurn him politely, not wanting to encourage conversation. It’s business as usual on the dark streets of Siem Reap. Later I shed a few more tears before bedtime. But I have gained hope that life in Cambodia will finally change for the better.

Tom Neal Tacker travelled courtesy of Bangkok Airways and Small Luxury Hotels.

Naked Facts:

Naked Routes:

Siem Reap is easily accessible via daily flights from Bangkok with Bangkok Airways. Tourist Visas can be purchased upon arrival. See www.bangkokairways.comfor flight details and reservations.

Naked Sleeps:

The Hotel de la Paix is located in the centre of Siem Reap in Sivatha Boulevard opposite the Central Market. See www.hoteldelapaix.com It is also a member of the Small Luxury Hotels of the World Group.

See www.slh.com for further information about hotel packages. Double rooms from USD$ 202.00 per night.

Naked Volunteers:

To visit the Hotel de la Paix Sewing Training Centre, inquire at the hotel. Visits to various English language schools may be similarly arranged.

See www.samveasna.org to arrange tours of Cambodia’s remaining wildlife wonders.

See www.greengeckoproject.org for further information or inquiries about donations.