Trekking around Iceland’s highlands in winter takes some fortitude. Is it worth it?

When I flew into Reykjavik’s Keflavik airport a fierce wind was blowing from the North Atlantic. Sleet was turning to snow before my eyes. I stepped outside the terminal building and faced into what felt like a cold shave with ice water and a dull blade. It hurt.

Iceland? What can I add to rumours of an early spring season in Iceland? The commonly held myth about Iceland being green and that Greenland conversely is white is basically wrong. Iceland is icy in winter, spring and autumn.

All I wanted to do was curl up under the duck down doona in my room at the Radisson Blu and hide from frozen reality, or at least until the weather cleared. Instead, after a short but cozy night’s sleep under that much loved doona (a sadly brief relationship) the following morning I boarded an outsized jeep contraption with seven other travellers and headed for the hills outside Reykjavik.

Our first weather report: Force Ten Gale, 25 metres per second winds, blowing snow with blizzard conditions. All sensible persons are advised to remain indoors under doonas. Actually I made up that last bit but if I was running Iceland’s weather bureau, this is the sort of advice I would find useful.

Until I visited Iceland, I didn’t know that wind velocity could be measured by increments of metres per second. I am accustomed to hearing wind speeds announced either in kilometres per hour or miles per hour, not metres per second. I ask one of our guides, ‘How fast is 25 metres per second?’ He responds, ‘Fast enough to blow you over.’ Hmm. ‘That’s fast,’ I say. ‘Yes, and it’s supposed to become faster.’ Hmm. ‘How much faster are the winds expected to reach?’ I ask. ‘Maybe 30 metres per second,’ he responds somewhat coldly. ‘That’s bad right?’ I ask. ‘Yes, fast enough to blow the jeep over and off the road. We may have to change our plans.’

I am not a masochist. I am not a masochist.

My mantra for the rest of a week in Icy-land.

On our initial day, we have a picnic. I like picnicking: cheese, bread, fruit, maybe a pate or terrine, a quiche perhaps? Chilled bottles of wine drunk in warm countryside.

Instead, we’re huddled under a canopy at the Thingvellir National Park, the site of Iceland and supposedly the world’s first parliament (the Thingvellir Viking Parliament) in a valley surrounded by low volcanic mountains which coincidentally share the fault line where western Iceland separates from eastern Iceland. Split politically right from the start. Same as it ever was.

The wind blows my instant chicken noodle soup clear out of the plastic mug. I put my back to the ceaseless icy wind, feeling shards of frozen sleet blast against my hooded parka. My hands are stiff with cold. Trying hard to respect the important austerity of Iceland’s most historic pilgrimage place, I can only think about how I can hold a second mug of soup out of the wind long enough for me to drink it.

This is not a picnic. This is a test of wills. Mine is losing against the elements.

We were scheduled to spend our fabulous first night on a ‘Winter Highlights’ expedition jeep trek across Iceland’s mountainous interior in a farmhouse near a beach popular with seals at Skagafjord on Iceland’s northern coast. Our guide reached the owner of the hut by phone warning him of our imminent arrival. The reply was daunting. ‘Don’t come. I can’t get the door open. The wind is blowing too hard against it.’

We continue driving up the spectacularly beautiful western coast road along Faza Bay on the Thjodvegur Road past to Hrutey and turn inland towards Akureyri then south some twenty kilometres to a different farmhouse better sheltered against the furious winds.

We arrive just before dark, enough time to cross country to visit an isolated ice cave. We chat about elves and trolls that are said to inhabit caves throughout Iceland. Evidently there are trolls in this cave. I don’t see trolls but I do see an extended white frozen tunnel, an extinct lava tube that recedes into darkness. If a coven of vampires were looking for a hang-out in Iceland, this would be prime habitat. I’m blue with cold. We’ve hiked a kilometre from where we left the super jeep across snowy fields to reach Dracula’s lair, a.k.a. troll cave.

The weather then took a turn for the worse.

The following day, conditions became absolutely appalling. We bounced from one snow drift to another. ‘White Out’ was the meteorological operative phrase for two whole days of driving. No horizon, no landscape, simply hour after hour of white nothingness which we traversed via GPS. The road had disappeared completely. We pressed on to a mountain hut, donned snowshoes and walked around a hot springs area while trying to remain standing so as not to fall into the scalding sulfurous water.

Outside the jeep all I could see was white. Inside the jeep, all I could see was white windows or fellow frozen passengers. Once we stopped to look out over a lake behind a dam, part of western central Iceland’s hydro-electric system. An Arctic fox ran quickly away from us, a smart move I thought It ran with purpose, probably to its den in a protected position out of the wind. For a moment, I felt jealous.

I am not a masochist. I am not a masochist.

On day three, while trying to ascend a dormant volcanic crater rim that overlooks other dormant volcanoes I felt my feet lifting off the ground. Through the driving snow I could almost see the hand in front of my face that was gripping a rock while the other was gripping a rope fence. I ran downhill back to the jeep, an easy feat as the wind was at my back for a change. I may have skipped a few steps and felt quite uplifted while doing it.

We visited another dramatic canyon riven by steam vents and waterfalls tumbling along its sheer cliffs. Only a few kilometres from our accommodation, I chose to walk back, relieved to be out of the jeep.

The wind was at my back and though I nearly froze solid, it was worth it just to come across a small herd of Icelandic horses corralled about a kilometre from the farmhouse where we stayed.

These amazingly hardy small horses are unique to Iceland. They can tough out the harsh winter conditions unlike other horses. Well insulated under shaggy coats, rear ends perpetually facing the biting winds, they look placid, as if this blizzard without end is just another walk in the park.

Interestingly, if an Icelandic horse is taken off the island, it’s never allowed to return. No other breed of horse is allowed on Iceland either. The local horses have the place all to themselves. Were I given to anthropomorphising animals, from the look on the faces of these horses, I would guess that they’re quite happy having Iceland all to themselves.

Each night we arrive at a different remote, deserted mountain hut, unpack our gear, prepare dinner and go to bed early. One night I cooked fried fish. Another night one of our guides prepared lamb stew. It had lamb, carrots and onions. We ate it again the next day for lunch but then we called it lamb soup.

Here’s an interesting titbit of information. Iceland’s national dish is rotten shark called ‘Hakarl’. Icelandic farmers like to eat it interspersed with straight shots of ‘Brennivin’, a.k.a. ‘Black Death’, the local version of aquavit.

To prepare: A gutted and headless shark is buried in a gravelly pit for several months. The putrid shark flesh is then air dried in a shed until it reaches cardboard stiffness. After months of curing, this delicacy is ready to eat. Rotten air dried shark reeks of ammonia and rancidity, sort of what I imagine very old cheap blue cheese that has been pissed on by a football team full of beer would taste like if it was left out of the fridge for a month or two. This national culinary delight invokes much patriotism among local people. It’s best not to criticise it in a room full of Icelanders as they may take offence and push you from a pub outside into a Force 10 gale. I have heard tales…

Iceland’s scenery is undeniably awe-inspiring, when weather permits seeing it. As the Earth cracks up the middle of Iceland, volcanoes, geysers and mountains with gushing waterfalls are created. One of the most famous waterfalls, Gullfloss, is an incredible sight. Nearly encased in cliffs of ice, torrents of water continue to run down a long canyon that ends in a drop off into a bluish abyss, it is truly impressive. With landscapes like these, it’s completely understandable that early Icelanders were wonder-struck by their shaky island.

By day four the weather began to clear a bit. Mount Hekla was nearby but we went higher up to a remote valley, ‘floating’ over snow in our super-Jeeps with their huge tyres from Hveravellir to Landmannalaugar where we stayed the night.

In summer, Landmannalaugar is justifiably popular with trekkers and campers. Hot springs bubble away near the single large accommodation hut. A lovely alpine river flows across the valley ringed by mountains and meadows.

We struggle to cross the swiftly running river. Its banks are now frozen, ice piled high on both sides. One Superjeep has to be towed out by another. Our two vehicles are rapidly encased in ice. Tyre pressure has to be lowered again. It takes 45 minutes to cross the river. It takes as long to clear the axles and tyres of solid ice when we get across to our accommodation.

In winter, Landmannalaugar is a vastly different place; empty and almost forlorn. The hut has no running water because of frozen pipes and no electricity. We hook up to car batteries to supplement the one hard working solar cell, essentially useless in these dark, cloudy conditions. To make matters worse, the outside bathroom toilet hut has nearly disappeared under snow.

To make the most of a fairly dire situation, we snowshoed up the valley, over a rocky ridge and across glacier crevasses. The guides seemed to know what they were doing so I went along for the hike, thankful not to be stuck in the back of a jeep again, or worse, in the hut where I was to spend the night. With diminishing winds, the land appeared stark in various shades of white. No one else was there. It’s a very remote place.

300,000 people live in Iceland, 200,000 of them reside in and near Reykjavik, which is essentially a large country town with a few funky bars equipped with sound systems playing lots of Bjork and a few other significant Icelandic bands unknown outside Iceland. The country is the size of Kentucky or Victoria, to give you an idea of land proportions compared to population. There is a lot of empty space, almost none of it arable. Now I know why as it’s mostly uninhabitable too.

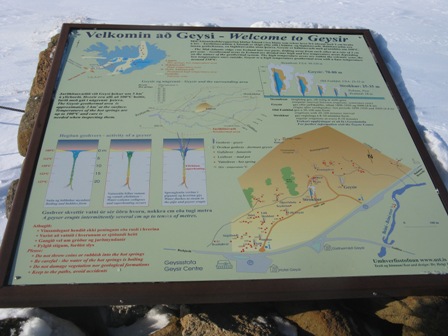

On our last day, we return to Reykjavik via Geysir. This is the original geyser, the mother of all geysers as the rest of the world’s geysers take their name from this one.

The incessant wind has mercifully begun to subside. Steam rising from Geysir lifts almost straight up into a pale blue sky, a vision I thought I’d never see again.

Some twenty kilometres outside Reykjavik we stop at a famous crater whose name I promptly forgot. The weather has turned fierce again, low clouds crept in after leaving Geysir. The wind has picked up and we’re back to normal. The crater is deep and forbidding. A troll would be happy living in it no doubt.

The six days of hard travel across Iceland’s interior during one of the season’s worst storms has been challenging but I’m glad I did it, if only to boast later that I survived the ordeal. Travel makes us all stronger doesn’t it?

I’ve come to understand a bit about the national character. To live, indeed prosper in this awful climate takes a special fortitude. No wonder Icelanders are known for being tough, stubborn and resourceful.

It’s certainly one of the world’s most curious countries.

I must mention that Icelanders are all related to one another, that they are either completely humourless or have bizarre senses of humour, that the country is flat broke with nary a Kroner to its name, that the value of its currency has fallen by 50% in two years and that its PM is a lesbian who is trying to put the house of Iceland back in working order while the men focus on drinking more beer and eating rotten shark bits.

I do like Iceland despite its off-putting wintry climate.

In many respects it’s my kind of country as it’s packed with eccentrics who are relatively harmless. There are hydrogen re-fill stations around Reykjavik for hydrogen fuelled vehicles. Wind and solar (solar would have to be very efficient technology, during my time in Iceland I saw the sun for all of five minutes) energy plants are being initiated as the usual geo-thermal plants are considered exhaustible; a curious notion on an island famously called the ‘Land of Fire and Ice’. You’d think there would be enough steam power in Iceland to keep the turbines turning for eons but the geologists beg to differ.

Finally, in case you’re wondering, it’s pronounced: Eh-ya-fee-yalla-th-yoa-kool and it’s not expected to blow again for another two hundred years. The ones to watch out for are Katla and Grimsvotn. When they blow up, flights may be disrupted for more than a year or two.

Tom Neal Tacker travelled courtesy of Thai Airways, SAS Airways and Mountain Guides Iceland.

Naked Facts:

See www.moutainguides.is for information about treks around Iceland. A very reputable company in business since 1996 with well trained guides and expert local knowledge.

Iceland’s airline operates from most European and many North American cities to Reykjavik’s Keflavik international airport. See www.icelandair.com for more information.

Naked Sleeps:

Reykjavik’s Radisson Blu 1919 hotel is highly recommended with far better than average hotel food and great service in an excellent location. See www.radissonblu.com/1919hotel-reykjavik for deals and bookings.