Afghanistan’s Turbulent History

Not all that long ago, as recent as the late 70s in fact, Afghanistan was a frequent stop on the so-called ‘hippy trail’ between Europe and Southeast Asia.

Kabul’s Chicken Street was famous for its backpacker hostels, cheap cafes and restaurants where hashish was freely available at cheap prices. Young travellers from round the world visited this mythical country as an important stop on their rite of passage to adulthood.

Women walked the streets of downtown Kabul heads bared, proud and free-spirited. University education was available, though primarily to the wealthy and well-connected elite. Young Afghan students with money could travel abroad to study, return home without fear of reprisal and contribute to the common good if they chose to do so. Commerce, albeit much of it derived from shady sources, was booming and the country was on a path to economic, social and religious freedom.

Sadly, that road to freedom was cruelly cut short.

If one country on this planet can be claimed as a prime example of history repeating itself, Afghanistan must be it.

Way back in the mid to late 19th century it was the hot point of conflict between the Russian and British empires. China, France and Prussia (Germany) also wanted their own piece of Afghanistan. The ‘Great Game’ of foreign espionage has its roots in Afghanistan.

Think now of notorious ‘whistle-blowers’ such as WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and ex-CIA apparatchik Edward Snowden leaking information about deep cover spy-hijinks and you have a notion of how many behind closed doors deals concerning Afghanistan featured in international foreign undercover communities more than a hundred years ago.

How did Afghanistan’s situation reach the crucial juncture it faces now?

Afghanistan’s descent into conflict and instability in recent times began with the overthrow of the king in 1973. Zahir Shah was in Italy for an eye operation when he was deposed in a palace coup by his cousin, Mohammad Daoud. Daoud declared Afghanistan a republic, with himself as president. He relied on the support of leftists to consolidate his power, and crushed an emerging Islamist movement.

Defining moment

But towards the end of his rule, he attempted to purge his leftist supporters from positions of power and sought to reduce Soviet influence in Afghanistan.

It was this that helped lead to a defining moment in Afghanistan’s recent history – the communist coup in April 1978, known as the Saur, or April Revolution. President Daoud and his family were shot dead, and Nur Mohammad Taraki took power as head of the country’s first Marxist government, bringing an end to more than 200 years of almost uninterrupted rule by the family of Zahir Shah and Mohammad Daoud. But the Afghan communist party, the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan – or PDPA – was divided, and splits emerged.

Ruthless leader

Hafizullah Amin, who had become prime minister, was opposed to Taraki, and in October 1979 Taraki was secretly executed, with Amin becoming the new president.

Amin, known for his independent and nationalist inclinations, was also ruthless. He has been accused of assassinating thousands of Afghans. To the Soviets in Moscow, he was looked upon as a threat to the prospect of an amenable communist government bordering Soviet Central Asia.

In a swift chain of events in December 1979, Amin was assassinated and the Soviet Red Army swept into Afghanistan. Babrak Karmal was flown from Czechoslovakia, where he was Afghan ambassador, to take over as the new president, albeit as a puppet leader acceptable to Moscow.

Million killed

The Soviet occupation, which lasted until the final withdrawal of the Red Army in 1989, was a disaster for Afghanistan. About a million Afghans lost their lives as the Red Army tried to impose control for its puppet Afghan government. Millions more fled abroad as refugees.

Groups of Afghan Islamic fighters – or Mujahideen – fought endlessly to try to force a Soviet retreat, with much covert support from the United States. After nearly 10 years the Soviet Union eventually withdrew, leaving in power President Najibullah, who replaced President Karmal as Afghanistan’s newest leader. He hung on for three years after the Red Army’s departure, but fell in 1992 as the United Nations was trying to arrange a peaceful transfer of power. The Mujahideen swept victoriously into Kabul. After a short interim measure, Professor Burhanuddin Rabbani became president of the new Islamic Republic.

Infighting

But their victory was soon soured by infighting as the Mujahideen factions failed to agree on how to share their new power. During the Soviet occupation it was predominantly rural areas that suffered military onslaught as the Red Army tried to flush out the Mujahideen.

But when the Mujahideen took over, it was the turn of urban areas to suffer from the conflict. This was especially true of the capital, Kabul, about half of which was literally flattened. Tens of thousands of civilians lost their lives, and the country slid more and more into a state of anarchy. It was towards the end of 1994 that the Taliban emerged in the southern city of Kandahar, the heart of Afghanistan’s Pashtun homeland. Their initial appeal – and success – was based on a call for the removal of the Mujahideen groups.

Taliban years

At first they succeeded in gaining control of Pashtun areas with little fighting. Mujahideen commanders defected to their ranks. But as their control spread to other, especially non-Pashtun areas, the fighting intensified. The Taliban went on to control about 90% of the country.

It was in 1996, as they captured Kabul, that much of the outside world first reacted in dismay to the Taliban’s extreme Islamic policies, especially towards the place of women in society. As Taliban control spread, the Western world intensified pressure on the Taliban to ban the growth of opium poppies, Afghanistan being the source of most opiates reaching Europe. The United States, in particular, also began their pressure on the Taliban to give up the militant Saudi, Osama Bin Laden, whom the Taliban described as their ‘guest’ in Afghanistan.

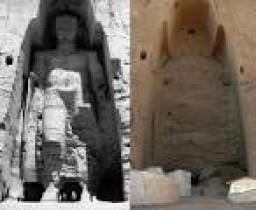

Earlier in 2001 the Taliban supreme leader, Mullah Mohammed Omar declared that two UNESCO World Heritage listed giant Buddhist statues in the western Bamiyan Valley were ‘un-Islamic’ and ordered their destruction.The global community was outraged at such senseless barbarism but was powerless to prevent it.

As of February 2014, attempts to rebuild the statues without official permission is jeopardising their UNESCO World Heritage status.

Washington blamed Bin Laden for masterminding the suicide attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York and the Pentagon in Washington on 11 September 2001. The following month the US and its allies began air attacks on Afghanistan which allowed the Taliban’s Afghan opponents to sweep them from power. Kabul was retaken in November and by early December the Taliban had given up their stronghold of Kandahar.

On 2 May, 2011 Osama Bin Laden was discovered hiding in Abbottabad, Pakistan and killed there by a US Special Ops team, thus ending one of the modern world’s longest running manhunts.

Road to elections

On 5 December 2001 Afghan groups agreed on a deal during international discussions in Bonn for an interim government, at the head of which Pashtun royalist Hamid Karzai was then sworn in. The Bonn conference, held under UN auspices, forged a political blueprint leading to elections scheduled for summer 2004.

In June 2002 a ‘Loya Jirga’, or grand council, elected Mr Karzai as interim head of state. A second ‘Loya Jirga’ in January 2004 adopted a new constitution. Since coming to power the US-backed Mr Karzai has survived at least ten assassination attempts. A number of his ministers and other senior figures have been less fortunate. Mr Karzai has been able to exert little control beyond the capital. Turf wars between local commanders have been a feature of the post-Taliban period. And the Taliban itself has re-emerged as a fighting force, worsening the security situation in the east and south-east. Thousands have died while violence and threats by the Taliban and other militants opposed to elections have contributed to landmark elections in 2004 and since. Those elections are notable primarily for corruption as Karzai enforces his hold on power through nepotism and vote buying.

As many aid organisations have collaborated in opening schools aimed at educating women, repairing damaged infrastructure and implementing a free press (local news, Afghan reality TV shows, more radio stations providing differing points of view, etc.), there remains a lot more to accomplish in helping guarantee the right of law and free speech in this deeply corrupt country.

What Next?

As USA and other military forces (Australia and the UK) withdraw from Afghanistan during this year, much opinion-making mainstream press editorial contributes to an ongoing debate about Afghanistan’s future.

National elections are scheduled for later 2014. Karzai has declared he won’t run for office this time. Who will be his successor? No one knows for sure.

As Karzai’s government has increased its control over more rural areas, his power base has also grown. But with international military support of Karzai’s government being gradually withdrawn this year, how his followers will deal with the re-emerging Taliban is also anyone’s guess.

No one really knows what will happen. Everyone who cares about Afghanistan ponders its hazy future.

One thing is certain.

Afghanistan will continue to exist in a stasis of uncertainty.

Hopefully, at some time in the near future this historically important country filled with environmental wonders will once again be open to travellers keen on learning more about them.

Afghanistan’s rich and varied cultures should be open to everyone willing to view firsthand its magnificent landscapes while studying its vibrant past.